4 Aug 2012

0 CommentsHave Lean Startups Helped Us Scale Larger Technology Companies?

Building larger technology companies is critical for our future economic well being, yet somehow we seem to pay more attention to the seed and startup phase. This post and a subsequent missive, Wisdom from Recent Waterloo Technology Acquisitions, aim to analyze some recipes for building technology businesses to scale first from the perspective of recent companies and then specifically through the lens of local acquisitions. This pair of posts will be based on extensive data, but the findings are intended to start discussion rather than be the last word.

The importance of building new, innovative, and large, companies can’t be underestimated regionally, provincially and nationally. Here in Waterloo, with perhaps 10 000 jobs at a single behemoth, Research in Motion, the notion of job creation is particularly topical simply to lessen our dependency on such a large company.

My sense is that, of late, most of the focus centres around making startups: small, energetic and entrepreneurial software, web and mobile companies, some simply building a mobile application. And, even with the current notion of Lean Startups or our Venture 2.0 approach, there is no question that building such early stage companies is probably an order of magnitude cheaper than it was back in the 1990’s While undoubtedly a good thing for all concerned – founders, investors and consumers all have so much more choice – has this led to a corresponding increase in new major businesses in the technology sector?

I see this as more of a discussion than a simple answer, and thus to start, I include the following table of my sense of how the numbers have changed over time. The following table provides some idea of how company formation has trended over the last 25 years, through the lens of scale rather than acquisitions:

[table “” not found /]NOTES ON DATA:

- Sources: public records, internet, personal recollections and interviews with 20 key ecosystem participants.

- The definition of “big” is purposely somewhat arbitrary (and perhaps vague). I am using a threshold of 50 employees or $10 million in revenues, which is probably more indicative of these startups becoming mid-sized businesses.

INITIAL INSIGHTS:

This data, while helpful, can never provide a complete answer. However, it can guide the conversation around what I see to be an important economic mission for our region and country – that is, building more significant technology businesses. I’m sure there are no easy answers, but in shaping policy, it is important to base decisions on informed debate and research.

To that end, I would offer the following thoughts:

- The current plethora of “lean startups” does not (necessarily) represent a clear path to growing those startups into larger businesses.

- I suspect that, in some ways, multiplying small startups can retard the growth of larger companies. That said, the data are insufficient to prove cause and effect.

- At the ecosystem level, we need to focus resource allocation beyond simple startup creation to include building more long term, and larger, technology businesses. Instead of spreading talent and other resources thinly, key gaps in senior management talent (especially marketing) and access to capital (B rounds and beyond) need to be resolved.

- Even in day to day discussion, the narrative must shift so that entrepreneurism isn’t just about startups, to make company building cool again.

Canada holds many smart, creative and hardworking entrepreneurs who will undoubtedly rise to the challenge of building our next generation economy. Meanwhile, I’d welcome comments, suggestions and feedback on how we can build dozens or more, instead of a handful, of larger technology companies in our region.

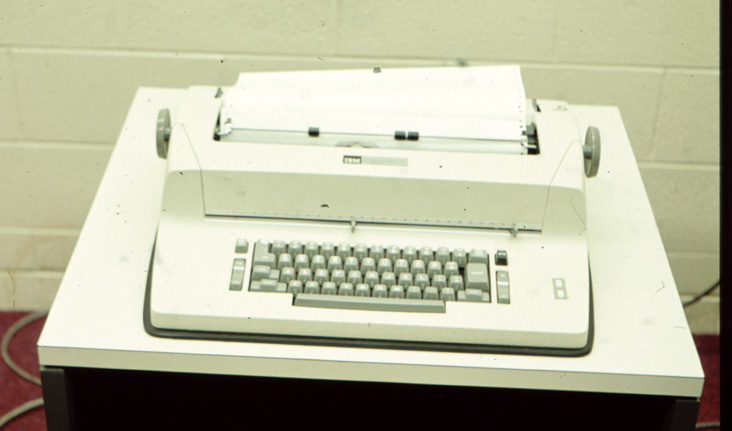

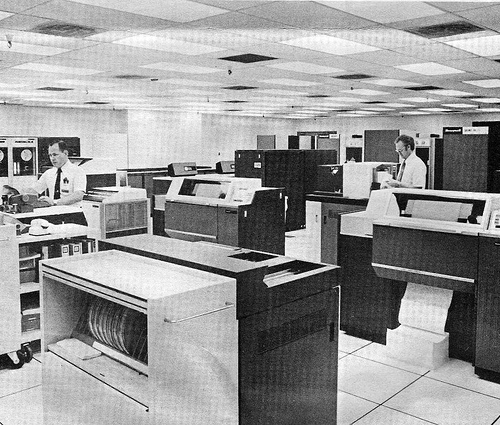

I first used computers at age 14, after being invited with a set of Math Contest winners to the University of Waterloo where I had the pleasure of using APL an early math-based timesharing system running on an IBM 360/44 . It is notable that, rather than learning the standard Fortran and programming on punch cards, I started programming using an IBM 2741, which is like an online IBM Selectric typewriter (typeball and all) connected via modem, with acoustic coupler, at 134.5 baud. Prior to this, I had read about computers and thought about them abstractly, but the plain truth is that computers were only accessible to a very small, privileged elite.

I first used computers at age 14, after being invited with a set of Math Contest winners to the University of Waterloo where I had the pleasure of using APL an early math-based timesharing system running on an IBM 360/44 . It is notable that, rather than learning the standard Fortran and programming on punch cards, I started programming using an IBM 2741, which is like an online IBM Selectric typewriter (typeball and all) connected via modem, with acoustic coupler, at 134.5 baud. Prior to this, I had read about computers and thought about them abstractly, but the plain truth is that computers were only accessible to a very small, privileged elite. Recently, a friend sent me the directory listing of an old backup tape for the Honeywell 6050 TSS system which reminded me that I first used email in 1975. Yes, we even had mailbox and mbox files way back then. Of course, the email system only connected the almost 1000 users of this computer, yet barely two years later my friend Bill Pase then working at IP Sharp Associates, connected me into a truly global email system run by that pioneering firm. This is primarily of interest because many people I talk to assume that email began in the late 1990’s.

Recently, a friend sent me the directory listing of an old backup tape for the Honeywell 6050 TSS system which reminded me that I first used email in 1975. Yes, we even had mailbox and mbox files way back then. Of course, the email system only connected the almost 1000 users of this computer, yet barely two years later my friend Bill Pase then working at IP Sharp Associates, connected me into a truly global email system run by that pioneering firm. This is primarily of interest because many people I talk to assume that email began in the late 1990’s. Around 1990, while CEO at

Around 1990, while CEO at

Avvey Peters from Waterloo’s

Avvey Peters from Waterloo’s  Alec Saunders, CEO of one of Canada’s most promising web/mobile startups,

Alec Saunders, CEO of one of Canada’s most promising web/mobile startups,  Peter Childs, an Ottawa social media strategist and tech luminary, has laid out a framework

Peter Childs, an Ottawa social media strategist and tech luminary, has laid out a framework

1 Jan 2014

0 CommentsIce Storms Highlight Canada’s Obsolete Infrastructure

As we enter 2014, well into the 21st Century, one lesson for me from the year just past was that Canada seems to be hobbled with 19th century infrastructure. Let me explain.

During 2013, my home in Ontario was subject to not one, but two, different ice storms – in April and December. Both brought down large chunks of trees and both caused multi-day electrical power outages. In decades, this is the first time I can recall losing power for more than 1 day. To have this occur twice, with a combined 8 days of power outage, in a single year is even more striking.

After the first ice storm in April, I recall discussing this with a European colleague who was surprised by the very notion of a power outage. From a European perspective, he suggested the last power outage, of any length, that he could recall was 30 years ago. This started me thinking about why the difference.

In Canada, we have always prided ourselves on being one of the world’s richest countries, with modern infrastructure. However, much of our infrastructure was built for a different time and need. Much of it is really a testament to truly inventive Victorian design. It was indeed wonderful but no longer makes sense in the 21st Century. So, why indeed do we still have most of our electrical power lines above-ground on poles, while the rest of the (rich) world generally buries them? Why do our railways still rely on switches that freeze in winter and need to be operated by workers with propane torches? Why is a city like Toronto paralyzed by a major rainstorm?

Our homes, utilities, drainage and much more was built for a world predating our current period of rapid climate change. Surprisingly there remain in this world Luddites, who bizarrely continue to deny the fact of climate change. While we still have much to learn, on-the-ground results are here for all to see.

I gained significant insight into these issues when as a Director of Gore Mutual Insurance Company, a leading property insurer, I attended an enlightening presentation by the poignantly named Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction (ICLR). This industry-funded organization is a world leader, collaborating globally in research and advocacy around the causes and solutions for large scale insurance losses, known in industry jargon as a Catastrophe or even a Cat.

ICLR gathers data and works with many academic researchers to increase both understanding and awareness of what causes insurance losses. The data shows that the last ten years have seen huge increases in the number of severity of large scale losses, particularly from damaging wind, water and ice events, which are all significantly driven by climate change.

For example, with increased wind events (typically tornadoes in this area of Ontario), a call for more homes to be built with windows structurally rated to withstand 200 mph wind events makes sense.

Furthermore, climate change means that rainfall in 1 hour can equal what used to occur over 24 hours or more, with flash floods ensuing. In such an environment, instead of our historic practice of getting rid of water as quickly as possible, it is better to slow it down and buffer the potential for flash flooding.

For me, the power outages are a metaphor for how we in Canadian society need to look at our infrastructure with a sense of long term vision. We really need to invest to upgrade utilities, transportation and drainage for the needs of the 21st century. This in no way takes away from the heroic efforts of Hydro workers over the holiday season. I’m simply surprised that attention has never been focused on the root cause and long term prevention.

In an era of political infighting and embarrassing city Mayors, I’m wondering where the leadership necessary to achieve this will come from?

.