6 Mar 2009

0 CommentsFail To Understand the Net Generation at Your Peril

The Net Generation (born 1977 to 1997), also known as Generation Y or the Millennials, is an ill understood lot. Don Tapscott, noted thought leader on digital technologies, is a real cheerleader for them in his recent book Grown Up Digital.

However, while some of his examples may represent the bleeding edge thought leaders of this generation, almost everything he says is well reasoned and researched. I would suggest this book is a must read for the rest of us who will watch this demographically dynamic generation increasingly dominate all aspects of our society, including business, culture, education, politics and entertainment. Many of us are looking at this generation from the perspective of the previously dominant demographic group known as Baby Boomers or Boomers (born 1946-1964), also known as the TV Generation. I would note that already, the Net Generation outnumbers the Boomers.

Perhaps the defining characteristic of this group is that they are the first generation to have been immersed from birth in digital technologies, such as the internet, computers and online media. Because of this, they are sometimes labelled “digitals“, with others who find these technologies more challenging to even baffling being called “analogues”. The Digitals don’t even think about technology, it is just part of the landscape for them. Analogues, by contrast, either avoid it like latter day Luddites or struggle to keep up with the Net Geners.

I’m part of an interesting hybrid group of people who were born analogue but has adopted many of the digitals characteristics. In essence, people like me might be described as a digital immigrant. Consider my digital pedigree:

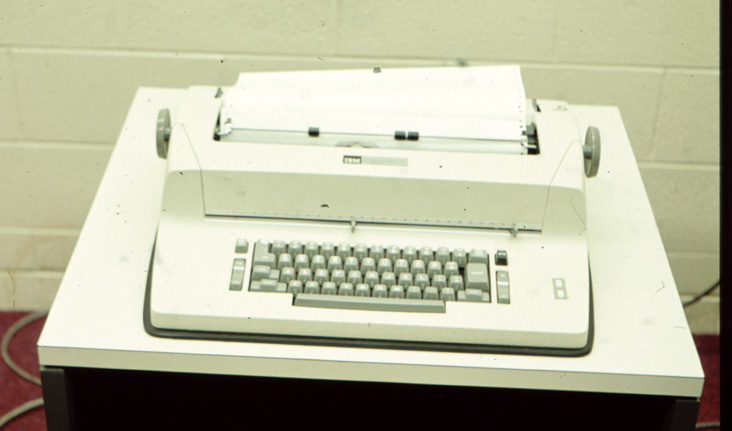

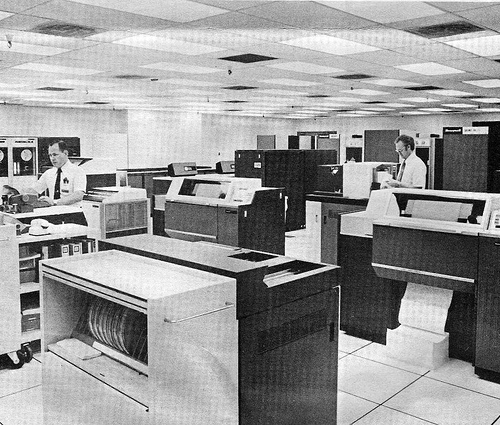

I first used computers at age 14, after being invited with a set of Math Contest winners to the University of Waterloo where I had the pleasure of using APL an early math-based timesharing system running on an IBM 360/44 . It is notable that, rather than learning the standard Fortran and programming on punch cards, I started programming using an IBM 2741, which is like an online IBM Selectric typewriter (typeball and all) connected via modem, with acoustic coupler, at 134.5 baud. Prior to this, I had read about computers and thought about them abstractly, but the plain truth is that computers were only accessible to a very small, privileged elite.

I first used computers at age 14, after being invited with a set of Math Contest winners to the University of Waterloo where I had the pleasure of using APL an early math-based timesharing system running on an IBM 360/44 . It is notable that, rather than learning the standard Fortran and programming on punch cards, I started programming using an IBM 2741, which is like an online IBM Selectric typewriter (typeball and all) connected via modem, with acoustic coupler, at 134.5 baud. Prior to this, I had read about computers and thought about them abstractly, but the plain truth is that computers were only accessible to a very small, privileged elite. Recently, a friend sent me the directory listing of an old backup tape for the Honeywell 6050 TSS system which reminded me that I first used email in 1975. Yes, we even had mailbox and mbox files way back then. Of course, the email system only connected the almost 1000 users of this computer, yet barely two years later my friend Bill Pase then working at IP Sharp Associates, connected me into a truly global email system run by that pioneering firm. This is primarily of interest because many people I talk to assume that email began in the late 1990’s.

Recently, a friend sent me the directory listing of an old backup tape for the Honeywell 6050 TSS system which reminded me that I first used email in 1975. Yes, we even had mailbox and mbox files way back then. Of course, the email system only connected the almost 1000 users of this computer, yet barely two years later my friend Bill Pase then working at IP Sharp Associates, connected me into a truly global email system run by that pioneering firm. This is primarily of interest because many people I talk to assume that email began in the late 1990’s. Around 1990, while CEO at MKS, I remember being at an X/Open meeting in Rome (where ironically, I ran into the self same Don Tapscott at the Capella Sistina of all places) we were working to develop many of the standards that would shape our modern, connected digital world. I vividly recall after hours discussions with other attendees about my misgivings about how an always-on, multi-media world would impact our overall quality of life. As you can imagine, Rome was a fantastic place to have that debate. Even more important, what was esoteric futuristic thinking 20 years ago has largely come true, for better or worse.

Around 1990, while CEO at MKS, I remember being at an X/Open meeting in Rome (where ironically, I ran into the self same Don Tapscott at the Capella Sistina of all places) we were working to develop many of the standards that would shape our modern, connected digital world. I vividly recall after hours discussions with other attendees about my misgivings about how an always-on, multi-media world would impact our overall quality of life. As you can imagine, Rome was a fantastic place to have that debate. Even more important, what was esoteric futuristic thinking 20 years ago has largely come true, for better or worse.

So, like Don Tapscott, having grown up with a constant backdrop of technology and really having been part of making this cultural form, I too am a cheerleader for this emergent generation. However, many others, the most famous being Mark Bauerlein, take a much dimmer view of this generation. His book The Dumbest Generation: How the Digital Age Stupefies Young Americans and Jeopardizes Our Future (Or, Don’t Trust Anyone Under 30) might well be the NetGen equivalent to Reefer Madness for the boomers. For me, this shows that many people totally misunderstand this talented generation. Sure, this generation has its flaws like any other, but like Don Tapscott, I’m pretty optimistic about it.

To give a taste of how fundamental, not to mention transformational, the Net Generation culture is, I list the 8 norms that Don Tapscott found and validated through his research. I would suggest that the following norms need to be underestand by the rest of society so that the generations can build bridges based on the strengths of each constituency. The alternative is to create a new generation gap based on misunderstandings, a neo-Luddite situation if you will.

Here are Don Tapscott’s 8 norms for the Net Generation:

- Freedom: this generation demands the freedom to choose at work, in education and the marketplace. And, for them, freedom is so ingrained that it is not an option.

- Cutomization: Growing up with computers and software, has made this the mashup generation. Everything from products to lifestyles can be customized. This generation is the living proof of Chris Anderson’s Long Tail phenomenon.

- Scrutiny: Living in the epicentre of the blogosphere, twitterverse, SPAM and nonstop marketing, high levels of filtering and scrutiny are the only defence of a generation which has made separating the signal from the noise an artform.

- Integrity: The laser beam clarity and transparency of an always-on, Google-indexed world has heightened this generation’s radar for anything that fails to ring true. When there is no place to hide, a lack of integrity becomes glaringly obvious with often severe consequences for people or companies who fail to understand this new reality.

- Collaboration: A generation that grew up on group work and online games, now has adopted global collaboration and teamwork like never before. The Net Generation’s digital connectivity likely are another nail in the coffin for command and control organizational design not to mention one-way traditional education models.

- Entertainment: Net Geners expect work to be fun and the line between work and play is much more blurry for this generation. This means that some of the pioneering approaches at the Googleplex, may well become mainstream in the coming years.

- Speed: Among fellow computer geeks, many used to pride themselves on speed and belittle the slower blink rate of the old fashioned world. Net Geners have taken this to extreme in their always-on, instantaneous world, expecting immediate feedback on everything they do. This could well be one of the biggest intergenerational challenges.

- Innovation: This is a generation of early adopters, living on the bleeding edge. Not content to have products and ideas pushed to them like 20th Century consumers, they push collaborative, user-generated approaches to even the products they consume.

In business, government or ordinary society, I think we ignore this tidal wave of new thinking totally at our own peril. The first step is to understand this generation. Then, and only then, can our generation harness the incredible energy, idealism, passion and drive to help us all build a better future.

Avvey Peters from Waterloo’s

Avvey Peters from Waterloo’s  Alec Saunders, CEO of one of Canada’s most promising web/mobile startups,

Alec Saunders, CEO of one of Canada’s most promising web/mobile startups,  Peter Childs, an Ottawa social media strategist and tech luminary, has laid out a framework

Peter Childs, an Ottawa social media strategist and tech luminary, has laid out a framework

Proper Economic Stimulus Can Lead To …

Proper Economic Stimulus Can Lead To … Significant Carbon Reduction

Significant Carbon Reduction

Brad Templeton

Brad Templeton

Jonathan @ Victoria/Mile 0

Jonathan @ Victoria/Mile 0 Jonathan sincerely appreciates all of the enthusiasm and support that he received along the way, especially from those individuals and families who deal with Autism every day, yet who found time in their otherwise heavily committed schedules to host local events, come out and meet him, and support him. Likewise, Jonathan is heartened by the many people from all walks of life, who, although they do not have direct connection to ASD, lent their efforts to the run and showed their concern and support for their fellow Canadians.

Jonathan sincerely appreciates all of the enthusiasm and support that he received along the way, especially from those individuals and families who deal with Autism every day, yet who found time in their otherwise heavily committed schedules to host local events, come out and meet him, and support him. Likewise, Jonathan is heartened by the many people from all walks of life, who, although they do not have direct connection to ASD, lent their efforts to the run and showed their concern and support for their fellow Canadians.

15 Mar 2009

0 CommentsWho Killed Canadian Venture Capital? A Peculiarly Canadian Implosion

The current economic meltdown has unleashed brutal forces acting on all aspects of the business world, but certainly innovative startups in fields like software, web, wireless, green technologies and life sciences are at grave risk. In Canada, our startups have generally been world class innovators, but severely underfunded when benchmarked against US and leading European countries.

Not only has the credit crunch forced most Angel Investors to the sidelines, but the supply of Venture Capital (VC) in Canada has contracted almost to the vanishing point.

Tomorrow’s Canadian Business documents this very well in VC Financing: Cold Realities.

Having started my first software company in the mid-1980’s, I am well aware that although VC money was available and well established in the Silicon Valley, VC money for knowledge-based startups such as mine was then nonexistent in Canada. Through the 1990’s, however, Canada started to build a cadre of new funds that showed early promise of replicating a US style VC funding ecosystem

In the early millennium when Verdexus investigated raising a institutional fund to fill a gap in the Canadian market with our “hands on” model and accessing global capital sources. It gave our partners a chance to look to VC best practices on a global basis and figure out how to apply to the Canadian context. While we didn’t proceed at that time, I’ve had the good fortune to work on projects with top VCs from the US and several European countries, giving me a global perspective on how Canadian Venture Capital measures up.

Sadly, I believe that the 2000/2001 tech bubble, or dot com meltdown, stopped the maturation of our VC industry in its tracks, a body blow from which the industry has never recovered. It is to this time that the root causes of our current VC meltdown can be traced. A few of the main reasons holding the VC industry back can be summarized as follows:

I will explore each of these causes in turn.

1. Labour Sponsored Investment Funds

Labour Sponsored Investment Funds (LSIFs, also known as Retail Venture Capital Funds), have been a particular sore spot, as a 2005 Globe and Mail Report on Business article “Labour-sponsored Love Lost” points out. Considered good public policy when launched in the late 1980’s, both Federal and Provincial governments gave individual (retail) investors a significant tax incentive (up to 35%) to invest up to $5 000 with a minimum 8 year hold period. In essence, many funds totalling hundreds of millions of dollars were raised by firms like VenGrowth, Covington and Growthworks as were numerous very small funds.

Lacking the inherent financial discipline imposed by typical venture capital structures, in which several “funds of funds” (legally dsignated as Limited Partners, or LPs) invest in a fund managed by a General Partner (or GP). The LPs in this sense have much leverage, not just in choosing their GPs, but also in ongoing oversight, not to mention the choice to re-invest in the next fund raised by the GPs. This LP/GP structure is the model employed world wide and has generally stood the test of time.

The thousands and thousands of retail investors in a typical LSIF exert no such control and hence we’ve seen Management Expense Ratios (MERs) as high as 4-6% versus the 2% private equity industry norm and Carried Interest (the portion of the investment gains shared by the fund) as high as 30% versus the 20% norm.

More importantly, although at its peak, more than half of Canadian VC money was in LSIF funds, returns were, as Doug Steiner says, “lousy.” How lousy? Studies show that average fund returns, also called Internal Rate of Return (IRR), are negative. The best fund appears to have produced a measly 1% IRR. In the US, funds aim for 30% and there is a long term track record of many funds in the 18-20% range.

Undoubtedly, individual investors didn’t have a lot at stake with those huge tax credits and it can be argued that LSIFs encouraged loads of job creation in the all important knowledge economy. All of that is true. My main concern is that the attraction of the LSIF model impaired the formation of a more mature VC ecosystem based on the normal LP/GP model mentioned above.

2. The Banker Effect

In the US, both in California’s Silicon Valley and in the Route 128 area around Boston, the VC industry has always been populated by a healthy mix of the financially oriented fund managers coupled with serial entrepreneurs who have founded and build technology startups. The composition of the partners at Canadian VC funds has always been different than this international norm, having many more banker types than operators. The experiences Jonathan Geist relates in the Canadian Business article are symptomatic of this difference. Too much focus on the numbers is like looking in the rear view mirror when startups need to be focused on the future – building market share, refining partnerships and developing strong go-to-market execution.

Again, I believe that this gap can be attributed to us being a less mature VC and startup ecosystem. In the late 1980’s and 1990’s finding seasoned technology startup operators would have been almost impossible. Most were still building their first startup. However, had things unfolded as they should have, many of the startup founders from the 1980’s and 1990’s should now be partners at Canadian VC firms. That didn’t happen because the dot com meltdown appeared to remove the ability to the industry to make changes or take risks. Ironically, this exacerbated an already more conservative VC culture here in Canada, and this more risk averse approach actually contributed to the lower IRRs seen when Canadian VCs are compared to their US or European peers.

3. Lack of International Money

The fledgling LP/GP VC industry of the 1990’s was funded by a relatively small ecosystem of LPs, such as OMERs, Caisse de Depot, Teachers, CPP, BDC, etc. Thus every VC fund was essentially not differentiated by its LP composition. In essence, a closed group of Canadian fund of funds all were chasing this same relatively small asset class. Furthermore, the relaxation of Canadian content rules coupled with these aforementioned low IRRs, sent the Canadian LPs looking elsewhere (mostly abroad).

What is the right recipe to change this situation? Quite simply, access to more global sources of money. The thousands of US, European and Gulf institutional fund of funds investors have largely ignored investments in Canadian VC funds. This is partially because of the chicken and egg of lower IRR returns. But, more fundamentally, it is primarily because the Canadian startup and VC ecosystem had low visibility to these international funds. Several years ago, I spoke to a large €6 billion LP fund at EVCA in Barcelona, that had investments in 40 tier 1 VC firms in each of the US and Europe. Ironically, that LP’s sense of the Canadian technology scene was limted to Nortel. Since Nortel hasn’t really been a star for many years. Clearly we have a long way to go market our great technology stories to the world.

The Way Forward

We already have a few outliers in our funding ecosystem. Being optimistic and entrepreneurial, I’m convinced that many talented individuals will find ways to, little by little, to invent and rebuild a healthy network of startup financing alternatives. As I’ve argued in other blog posts, there is a role for governments. However, that role isn’t to pick winners or to enter the VC business directly, rather it is to be a catalyst to the process by streamlining (securities) regulation and taxation.

As a stakeholder in the success of knowledge-based startups, what do you think?

Please share your comments.