1 Jan 2012

0 CommentsDennis MacAlister Ritchie (1941-2011) – My Inspiration by a Great Man Who Quietly Shaped an Industry

NOTE: The intrusion and profusion of projects in my life, has prevented blogging for some time. As 2011 draws to a close, I thought I needed to make an effort to provide my perspective on some important milestones in my world.

Back in October, when Rob Pike posted on Google+:

I just heard that, after a long illness, Dennis Ritchie (dmr) died at home this weekend. I have no more information.

I trust there are people here who will appreciate the reach of his contributions and mourn his passing appropriately.

He was a quiet and mostly private man, but he was also my friend, colleague, and collaborator, and the world has lost a truly great mind.

Although the work of Dennis Ritchie has not been top of my mind for a number of years, Rob’s posting dredged up some pretty vivid early career memories.

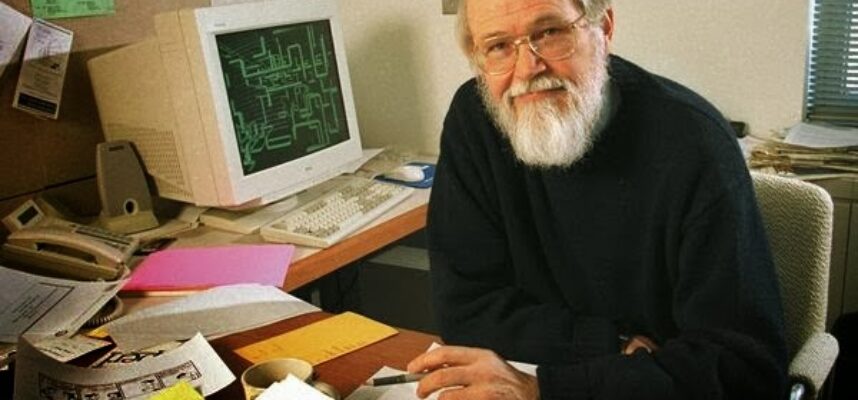

As the co-creator of UNIX, along with his collaborator Ken Thompson, as well as the C Programming Language, Dennis had a huge and defining impact on my career, not to mention the entire computer industry. In short, after years as a leader in technology yet market laggard, it looks like in the end, UNIX won. Further, I was blessed with meeting Dennis on numerous occasions and, to that end, some historical narrative is in order.

Back in 1973, I got my first taste of UNIX at the University of Waterloo, serendipitously placing us among a select few who tasted UNIX, outside of Bell Labs, at such an early date. How did this come about? In 1972, Steve Johnson spent a sabbatical at University of Waterloo and brought B Programming Language (successor to BCPL and precursor to C, with all its getchar and putchar idiom) and yacc to the Honeywell 6050 running GCOS that the University’s Math Faculty Computing Facility (MFCF) had installed in the summer of 1972. Incidentally, although my first computer experience was in 1968 using APL on IBM 2741 terminals connected to an IBM 360/50 mainframe, I really cut my “hacker” teeth on “the ‘Bun” by writing many utilities (some in GMAP assembler and a few in B). But, I digress . .

Because of the many connections made by Steve Johnson at that seminal time, University of Waterloo was able to get Version 5 UNIX in 1973 before any real licensing by Western Electric and their descendents by simply asking Ken Thompson to personally make a copy on 9 track magnetic tape. My early work at Computer Communications Networks Group (CCNG) with Dr Ernie Chang attempting to build the first distributed medical database (shades of Personal Health Records and eHealth Ontario?) led me to be among the first to get access to the first Waterloo-based UNIX system.

The experience was an epiphany for me. Many things stood out at the time about how UNIX differed from Operating Systems of the day:

- Compactness: As described by a fellow UNIX enthusiast at the time, Charles Forsyth, it was amazing that the entire operating system was barely 2 inches thick. This compared tot he feet of listings for GCOS or OS/360 made it a wonder of minimalistic compact elegance.

- High Level Languages: The fact that almost 98% of UNIX was coded in C with very little assembler, even back in the days of relatively primitive computing power, was a major breakthrough.

- Mathematical Elegance: With clear inspiration from nearby Princeton and mathematical principles, the team built software that for the day was surprisingly mathematically pure. The notion of a single “flat file” format containing only text, coupled with the powerful notion of connecting programmes via pipes made the modular shell and utility design a real joy to behold.

- Extensible: Although criticized at the time for being disc- and compute-intensive and unable to do anything “real time”, UNIX proved to have longevity because of a simple, elegant and extensible design. Compare the mid-1970’s UNIX implementations supporting 16 simultaneous users, on the 16-bit DEC PDP-11/45 with 512KB (note that this is “KB” not “MB”) with today’s Windows quad-core processors that still lock out typing for users, as if prioritized schedulers had never been invented.

At Waterloo, I led a team of UNIX hackers who took over an underused PDP-11/45 and create Math/UNIX. On that system, many top computer talents of today adopted it as their own, including Dave Conroy, Charles Forsyth, Johann George, Dave Martindale, Ciaran O’Donnell, Bill Pase and many more. We developed such innovations as highly personalized security known as Access Control Lists, Named Pipes, file and printing networked connections to Honeywell 6050 and IBM mainframes and much more. Over time, the purity of UNIX Version 7 morphed into the more complex (and perhaps somewhat less elegant, as we unabashedly thought at the time) Berkeley Systems Distribution (BSD) from University of California at Berkeley. That being said, BSD added all-important networking capabilities using the then nascent TCP/IP stack, preparing UNIX to be a central force in powering the internet and web. As well, BSD added many security and usability features. My first meeting with Dennis Ritchie was in the late 1970’s when he came to speak at the U of W Mathematics Faculty Computer Science Club. Having the nicest car at the time, meant that I got to drive him around. I was pleasantly surprised at how accessible he was to a bunch of (mostly grad) students. In fact, he was a real gentleman. We all went out to a local pub in Heidelberg for the typical German fare of schnitzel, pigtails, beer and shuffleboard. I recall him really enjoying a simple time out with a bunch of passionate computer hackers. I, along with Dave Conroy and Johann George, moved on from University of Waterloo to my first software start up, Mark Williams Company, in Chicago, where I wrote the operating system and many utilities for the UNIX work alike known as Coherent. Mark Williams Company, under the visionary leadership of Robert Swartz, over the years hosted some of the top computer science talen in the world. Having previously worked with Dave Conroy on a never completed operating system (called Vesta), again the intellectual purity and elegance of UNIX beckoned to me to build Coherent as a respectful tribute to the masters at Bell Labs. Other notable luminaries who worked on Coherent are Tom Duff, Ciaran O’Donnell, Robert Welland, Roger Critchlow, Dave Levine, Norm Bartek and many more. Coherent was initially developed on the PDP-11/45 for expediency and was running in just over 10 months from inception. A great architecture and thoughtful design, meant that it was quickly ported to the Intel x86 (including the IBM PC, running multi-user on its non-segmented, maximum of 256KB of memory), Motorola 68000 and Zilog Z8001/2. The last architecture enabled Coherent to power the Commodore 900 which was for a time a hit in Europe and, in fact, used by Linus Torvolds as porting platform used in developing Linux. I got to meet Dennis several times in the context of work at Coherent. First, in January 1981 at the then fledgling UNIFORUM in San Francisco, Dennis and several others from Bell Labs came to the Mark Williams suite to talk to us and hear more about Coherent. I remember Dennis reading the interrupt handler, a particularly delicate piece of assembler code and commenting about how few instructions it took to get through the handler into the OS. Obviously, I was very pleased to hear that, as minimizing such critical sections of the code is what enhanced real time response. The second time was one of my first real lessons in the value of intellectual property. Mark Williams had taken significant measures to ensure that Coherent was a completely new creation and free of Bell Labs code. For example, Dave Conroy‘s DECUS C compiler, written totally in assembler, was used to create the Coherent C compiler (later Let’s C). Also, no UNIX source code was ever consulted or present. I recall Dennis visiting as the somewhat reluctant police inspector working with the Western Electric lawyers, under Al Arms. Essentially, he tried all sorts of documents features (like “date -u” which we subsequently implemented) and found them to be missing. After a very short time, Dennis was convinced that this was an independent creation, but I suspect that his lawyer sidekick was hoping he’d keeping trying to find evidence of copying. Ironically, almost 25 years later, in the SCO v. IBM lawsuit over the ownership of UNIX, Dennis’s visit to Mark Williams to investigate Coherent was cited as evidence that UNIX clone systems could be built. Dennis’s later posting about this meeting is covered in Groklaw.  In 1984, I co-founded MKS with Alex White, Trevor Thompson, Steve Izma and later Ruth Songhurst. Although the company was supposed to build incremental desktop publishing tools, our early consulting led us into providing UNIX like tools for the fledgling IBM PC DOS operating environment (this is a charitable description of the system at the time). This led to MKS Toolkit, InterOpen and other products aimed at taking the UNIX zeitgeist mainstream. With first commercial release in 1985, this product line eventually spread to millions of users, and even continues today, surprising even me with both its longevity and reach. MKS, having endorsed POSIX and x/OPEN standards, became an open systems supplier to IBM MVS, HP MPE, Fujitsu Sure Systems, DEC VAX/VMS, Informix and SUN Microsystems.

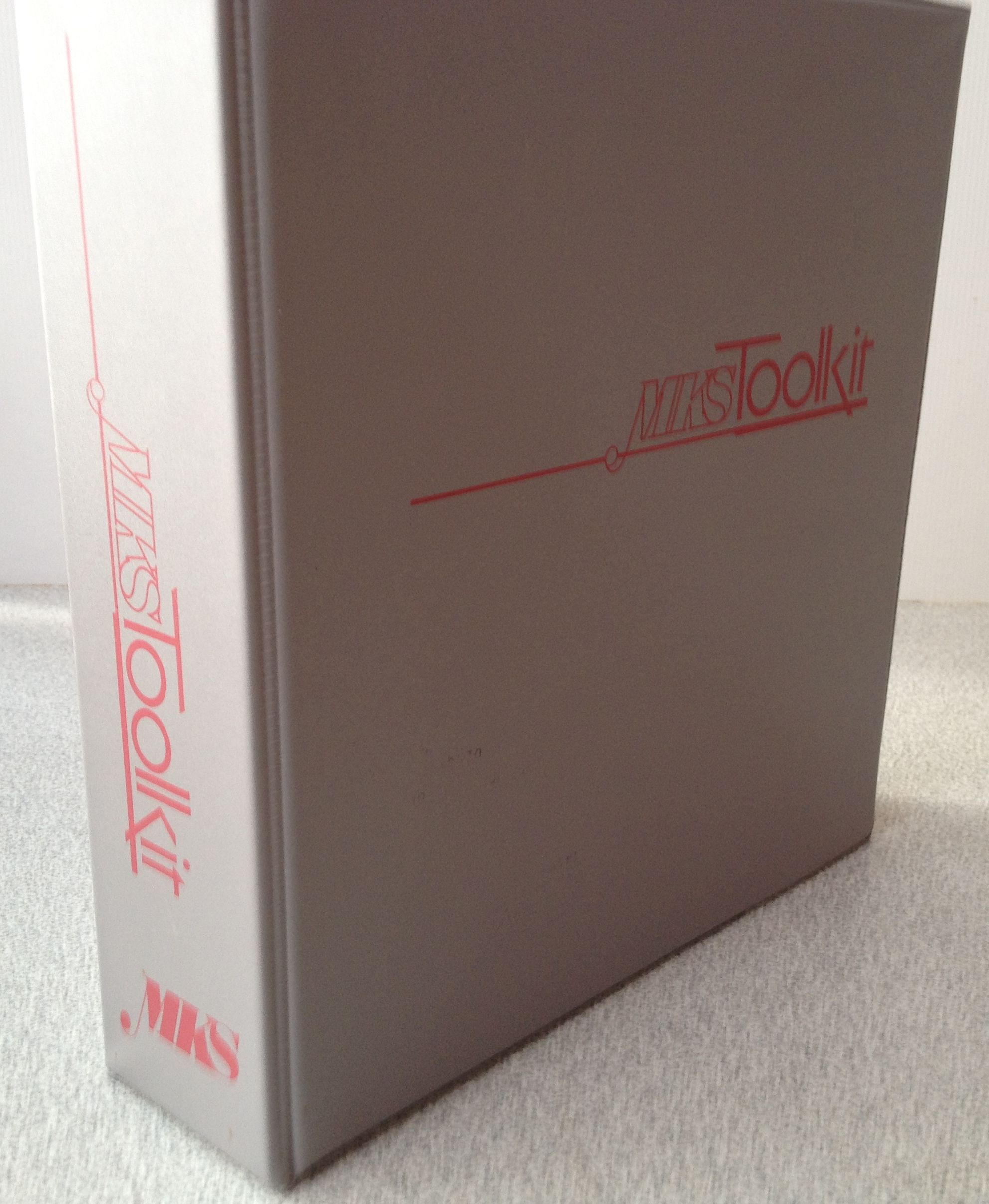

In 1984, I co-founded MKS with Alex White, Trevor Thompson, Steve Izma and later Ruth Songhurst. Although the company was supposed to build incremental desktop publishing tools, our early consulting led us into providing UNIX like tools for the fledgling IBM PC DOS operating environment (this is a charitable description of the system at the time). This led to MKS Toolkit, InterOpen and other products aimed at taking the UNIX zeitgeist mainstream. With first commercial release in 1985, this product line eventually spread to millions of users, and even continues today, surprising even me with both its longevity and reach. MKS, having endorsed POSIX and x/OPEN standards, became an open systems supplier to IBM MVS, HP MPE, Fujitsu Sure Systems, DEC VAX/VMS, Informix and SUN Microsystems. During my later years at MKS, as the CEO, I was mainly business focussed and, hence, I tried to hide my “inner geek”. More recently, coincidentally as geekdom has progressed to a cooler and more important sense of ubiquity, I’ve “outed” my latent geek credentials. Perhaps it was because of this, that I rarely thought about UNIX and the influence that talented Bell Labs team, including Dennis Ritchie, had on my life and career. Now in the second decade of the 21st century, the world of computing has moved on to mobile, cloud, Web 2.0 and Enterprise 2.0. In the 1980’s, after repeated missed expectations that this would (at last) be the “Year of UNIX” we all became resigned to the total dominance of Windows. It was, in my view, a fatally flawed platform with poor architecture, performance and security, yet Windows seemed to meet the needs of the market at the time. After decades of suffering through the “three finger salute” (Ctrl-ALT-DEL) and waiting endlessly for that hourglass (now a spinning circle – such is progress), in the irony of ironies UNIX appears on course to win the battle for market dominance. With all its variants (including Linux, BSD and QNX), UNIX now powers most of the important Mobile and other platforms such as MacOS, Android, iOS (iPhone, iPad, iPod) and even Blackberry Playbook and BB10. Behind the scenes, UNIX largely forms the architecture and infrastructure of the modern web, cloud computing and also all of Google. I’m sure, in his modest and unassuming way, Dennis would be pleased to witness such an outcome to his pioneering work.

During my later years at MKS, as the CEO, I was mainly business focussed and, hence, I tried to hide my “inner geek”. More recently, coincidentally as geekdom has progressed to a cooler and more important sense of ubiquity, I’ve “outed” my latent geek credentials. Perhaps it was because of this, that I rarely thought about UNIX and the influence that talented Bell Labs team, including Dennis Ritchie, had on my life and career. Now in the second decade of the 21st century, the world of computing has moved on to mobile, cloud, Web 2.0 and Enterprise 2.0. In the 1980’s, after repeated missed expectations that this would (at last) be the “Year of UNIX” we all became resigned to the total dominance of Windows. It was, in my view, a fatally flawed platform with poor architecture, performance and security, yet Windows seemed to meet the needs of the market at the time. After decades of suffering through the “three finger salute” (Ctrl-ALT-DEL) and waiting endlessly for that hourglass (now a spinning circle – such is progress), in the irony of ironies UNIX appears on course to win the battle for market dominance. With all its variants (including Linux, BSD and QNX), UNIX now powers most of the important Mobile and other platforms such as MacOS, Android, iOS (iPhone, iPad, iPod) and even Blackberry Playbook and BB10. Behind the scenes, UNIX largely forms the architecture and infrastructure of the modern web, cloud computing and also all of Google. I’m sure, in his modest and unassuming way, Dennis would be pleased to witness such an outcome to his pioneering work.

The Dennis Ritchie I experienced was a brilliant, yet refreshingly humble and grounded man. I know his passing will be a real loss to his family and close friends. The world needs more self-effacing superstars like him. He will be greatly missed.

I think there is no more fitting way to close this somewhat lengthy blogger’s ramble down memory lane than with a humorous YouTube pæan to Dennis Ritchie Write in C.

5 Jan 2012

0 CommentsPost-acquisition Reflections on MKS

First of all, I would like to congratulate Phil Deck, Michael Harris and the entire team for finding both a fabulous new home for MKS, but also one which represents a significant strategic financial transaction, valuing MKS at just over 4 times estimated FY2011 sales.

Many people have asked for my perspective. In short, I continue to view the acquisition as favourable to customers, employees, Waterloo and its shareholders. To delve further, this article, written from my own perspective, gives both background and some lasting observations and universal lessons from MKS.

Over the last decade, MKS largely sat out the wave of consolidations in Applications Lifecycle Management (ALM, that builds on the earlier category of Software Configuration Management), for example:

The aforementioned almost $5 billion acquisition binge represented a huge shift in the ALM market dynamics. By 2011, a new driver for acquisitions had emerged. As engineered products start to contain more software value than traditional hardware, customers requirements in the Product Lifecycle Management space started to converge with the Application Lifecycle Management space. This blending and merging of categories, fuelled by the trend to software being the dominant product differentiator, led to the acquisition of MKS by PTC and may portend more activity as these spaces continue to consolidate. Because PTC is moving into a new, but adjacent market category, that means that the domain expertise from the MKS product teams will be critical to PTC‘s long term success.

Could MKS have remained independent? My sense is, in the longer term, no. In the 1990s, a company could IPO on the NASDAQ at around $20 million revenues. Today, that number is over $100 million, and MKS at acquisition had about $75 million revenues. Perhaps further acquisitions might have accelerated getting to scale, but without a NASDAQ public currency that would have been difficult. Therefore, that’s a key reason why the PTC acquisition is such a home run win for MKS.

MKS built great value as a significant global software business over its 27 years of pre-acquisition existence. I’m very pleased that, unlike some early stage start up acquisitions, this likely means that PTC will continue to see Waterloo as a base for further expansion based around the solid product R&D team. In that sense, it’s great news for the region’s economy and something I’m very happy to see.

I wanted to reflect on a few themes that I’ve seen play out over MKS‘ long history – both lessons learned and some principles that might help some of the current crop of start ups grow into global businesses headquartered in Waterloo.

PIVOTS

MKS definitely was a company that had the proverbial “9 lives”. Using the au courant start up lingo, these were critical “pivots”. The number of pivots arises partly because MKS was a multi-product company and even more so because MKS was a first generation of software company in Canada, before clear rules to build such a knowledge based business had been formulated. Achieving company growth means many battles fought (and not all successfully) to win the war of business success. I’ve also come to learn that timing can trump even the most gifted product strategy work or execution attempts. As a result, ultimate success can be seasoned by many failures along the way to that success.

The following summarizes some of those 9 lives inside MKS:

Although there were many more than the above sample 9 lives, I think that the twists and turns to build a real business are a critical lesson for today’s companies. At Verdexus we today ascribe to the pure play strategy for startups (less capital required, more focus and easier to explain to investors). Nonetheless, there is much to be said for building a strong base around multiple product innovation.

WORLD CLASS TEAM

While the players have changed over the years, MKS has been blessed by an amazing group of employees, and not just in senior management. For example, at the time of our proposed NASDAQ IPO in early 1997, the investment bankers from Hambrecht & Quist in San Francisco mentioned, upon meeting our senior team, that this was amongst the strongest they have ever seen. Part of this came from hiring both from US and Canada (See GLOBAL APPROACH below) and that includes non-Canadian executives such as Tobi Moriarty, Mike Day, Holger Schmeidefeldt and Frank Schröder. We really did take to heart the maxim that great leadership came from a strong team, as I discussed in “The Power of Two (Or Three)“.

A positive environment led to better gender balance and better results. For example, in 1996 the senior management team of 7, included 3 women. Such a balance, sadly rare even today, led to enhanced results and sense of opportunity across the entire staff.

I am most pleased by the many talented employees at MKS, from co-op students onwards, who have gone on to incredible heights of achievement. I am continually discovering another company that has been built by talent that got its first state of the software business at MKS. I think one approach that has real merit, was the notion to bring top global talent into the business, in part for the mentoring effect this has on other employees. Considering the Waterloo ecosystem in the 1990s, this was particularly helpful in building previously thin functional areas such as marketing and product management.

Finally, given recent media attention to weak and/or non-independent boards, I was pleased to have a board that was both global and always able to hold management accountable. As CEO, I can remember many uncomfortable moments when I, or other management team members, were seriously challenged, and that is exactly how it should be.

GLOBAL APPROACH

Perhaps because I had my first software start up experience in the US (building Coherent), it only seemed natural to focus on the entire North American market, and ignore conventional advice to start with the local region, province or country. Even in the very earliest days of MKS Toolkit, when products were shipped by mail and advertised in physical magazines, we realized that every promotional dollar went much farther in the US versus just focusing on Canada. The led to perhaps the first customer of MKS Toolkit being AT&T Bell Labs, which I believe contributed to MKS becoming known across North America in developer circles. The use of 800 toll free numbers across US and Canada, coupled with email, allowed us to work and act like a US company. To me, it always felt similar to the Israeli model for tech companies.

By the 1990s, although we had distributors in Europe (and a small few in Asia), we decided invest heavily in the European market, first from a beachhead in Germany and then the UK. By 2000, Europe represented about 35% of the company’s revenues which later proved a strong hedge to the US-centric meltdown that started in 2000.

CAPITAL

Although MKS pre-dated Canadian venture capital, it did access the capital markets through various vehicles, such as the Special Warrant and IPO, that were common in the 1990s. During my tenure, about $40 million was raised, and I believe that the whole lifecycle raise was in excess of $50 million. During the 1990s, this was the normal cost to build a major entrprise software company to full scale. Today, while our Venture 2.0 methodology and the Lean Startup approach lessens the capital requirements, I still believe that, over the longer term, building a significant business takes much more capital than people realize.

One consequence of this, coupled with the more limited capital available in Canada (at least Ontario), is the tendency of technology companies to exit early – when they are partly built start ups rather than full businesses. In a way, this means that acquiring companies are really only getting a product and development team in a form of outsourced innovation. The downside of this model would seem to me to be the creation and maintenance of far fewer jobs in our region. I would love to see a rigorous study of this effect. In fact, my next post will explore the stage and timing of significant Waterloo region technology company acquisitions.

GROWTH BY ACQUISITIONS

Although MKS never had the NASDAQ public currency, being public on the TSX enabled the 7 acquisitions I was involved in. I would say that acquiring companies was a real learning curve. On balance, we managed to increase our acquisition capabilities over time, but always the results took longer than expected. For example, the acquisition of the AS/400 business from Silvon brought MKS many of today’s largest customers (e.g. HSBC), but the anticipated synergies took 2-3 years or more rather than the predicted 18 months to materialize.

The bigger issue, beyond building M&A expertise, is that today it is harder for companies to go public and have market liquidity for acquisitions than in the 1990s. I’m not sure if 21st century capital markets will ever return to a state where that is again possible.

FUN AND CAMARADERIE

Last, but definitely not least, most days whether travelling to engage the world or back in the office, people had a lot of fun while building a great business. The right mix of “work hard, play hard” can lead to a better overall experience that, in so many ways, enhances overall performance. And, we had some pretty great parties, whether at product launches in California or Europe or simply back home celebrating key milestones for MKS.

SUMMARY

The above observations represent but a small taste of my thoughts regarding the recent MKS acquisition. My hope is that the Waterloo tech ecosystem will witness many more companies being able to transcend the start up phase to become globally leading businesses. The future of our country and region depends on it.